Globalization

This is part two of an eight-part series on trade and how changes in policy might affect the local economy.

One of the more interesting characters President Donald J. Trump has brought into the White House is Stephen K. Bannon, a top advisor to Trump with the job title of Chief Strategist.

Bannon is a former Navy officer, Wall Street financier, former chairman of Breitbart News, and a former Hollywood producer who derives some of his income from royalties on the TV series "Seinfeld." To his enemies, he is a white nationalist, a fascist, a Nazi, even though these are characterizations he rejects and the evidence to support the labels is suspect. He calls himself an "economic nationalist."

His epiphany came, he has said, during the 2008 financial crisis. His father lost $100,000 when he sold his AT&T stock (without consulting a financial advisor or anyone in his family). When Bannon observed the ability of Wall Street CEOs to walk away from the crisis unscathed while hardworking Americans such as his father were hurt, he was incensed. Bannon believed (and he's far from alone in this perception) that Wall Street tycoons perpetrated a fraud while profiting from the meltdown.

The crisis set Bannon on the path of an economic ideology he believes will protect the working people of America from the elites of a globalized economy. When Bannon and Trump met, in many ways, they were soulmates. Without using the term, Trump was probably an economic nationalist before he decided to run for president.

Trump doesn't call himself an economic nationalist. He just says, "We're going to put America first." That's an emotionally more powerful term that has resonated with voters.

If we're going to talk about trade over the next few days and understand how the Trump Administration's policies may change the economics of Genesee County, if not the entire world, it would be helpful to understand what Trump and Bannon believe and where that fits into the history of economics.

When Trump talks about putting America first, the message resonates with a subset of his supporters who are against globalization.

The word globalization means different things to different people. To nationalists, it seems to mean a process by which countries begin to surrender their sovereignty to international organizations such as the United Nations, World Trade Organization and the World Court. To most economists, it means the world developing more tightly coupled economic ties and becoming more interdependent through trade with no need to trample national sovereignty.

The anti-globalist believe countries can best protect their sovereignty by restricting trade. That approach is called protectionism.

Many economists think the whole idea of protectionism was smashed by Adam Smith, the Scotsman who published "The Wealth of Nations" in 1776. "The Wealth of Nations" in a real sense marked the birth of economics as a course of study. Until Smith's monumental work, how trade worked was viewed through a lens of thinkers known as mercantilists. For the mercantilists, trade was a zero-sum game -- for every winner, there was a loser, for one side of a trade to gain, the other said had to fall behind. For that reason, mercantilists believed that governments needed to plan the trade of their countries and if necessary raise barriers to trade to protect homegrown production.

Smith said that simply isn't true. Smith argued that to force people to make at home what could be made more cheaply in another country was a waste of resources because the people doing less productive work could better spend their time doing things that made a greater contribution to the local economy.

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy. The tailor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a tailor. The farmer attempts to make neither the one nor the other, but employs those different artificers.

The best economy, according to Smith, is one where each person is free to maximize his own productivity. By laboring in one's own interest, Smith observed, people contribute to the greater public good though that is not their true intention. His famous phrase from this passage is "the invisible hand," or that which guides the whole economy toward greater good through a series of self-interested actions by individuals.

That is the essence of the free market.

Economist David Ricardo would expand on this observation with his theory of comparative advantage. Ricardo argued that two nations benefit when each engaged in their greatest economic capacity and then trade the results of that output. Ricardo's example involves a bit of math, but basically if one country has an advantage over another in making both wine and cloth, but the greater advantage lies in wine, then the wine country should make wine and trade for cloth and the country weaker in both wine and cloth should make cloth and trade for wine. In this way, both countries are more productive together than each doing their own thing.

Comparative advantage comes right down to the county level and even the individual farm level, said Craig Yunker, CEO of CY Farms. If one farmer has better ground for raising cattle and another farmer has better land for grains, they would both be foolish to try to be in the cattle and grain business. They are better off putting most of their effort into cattle for one and grain for the other (even if they both do a little cattle or a little corn).

The same applies to international trade, Yunker said.

"There are factories that have been closed for 100 years," Yunker said. "They don't make buggy whips anymore. There are cars being made in Mexico, but the technology comes from the United States. There are probably more cars being sold worldwide because of the expansion of production and we all benefit."

The way Pete Zeliff sees it though is the United States has a lot of advantages that it can use to grow manufacturing regardless of what the rest of the world does. Zeliff, owner of p.w. minor and a member of the Genesee County Economic Development Center Board of Directors, points to our lower cost of chemicals and our lower cost of energy, especially since the birth of the shale gas industry. That will make the United States more competitive in manufacturing, he said.

"The price of natural gas will be below $4 for the next 30 years," Zeliff said. "That will make us the most competitive country in the world. We're energy independent with the lowest cost of energy in the world. We can source 85 percent (of inputs for manufacturing) right here. The rest of the world cannot."

Even with Smith pointing the way to the value of free trade, many world leaders couldn't shake the appeal of protectionist policies because the benefits of free trade are incrementally diffused over time and across populations while the occasional costs of free trade are more visible (see: The Fruits of Free Trade (pdf)).

The world got itself into a lot of trouble through protectionist policies in the early 20th century, with protectionism contributing to a worldwide depression and eventually a global war. That created a greater realization that developed nations needed to find ways to cooperate.

That led to The Bretton Woods Conference, held in 1944 in New Hampshire and attended by delegates from 44 Allied nations, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947.

Bretton Woods led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund and of the organization that eventually became the World Bank (the late Barber Conable, Batavia's representative in Congress in the 1970s, became president of the World Bank in 1986).

GATT governed trade among signatories until the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1993.

The roots of these agreements were planted by events of the previous 40 years. The chaos that followed World War I was predicted by economist John Maynard Keynes in his book the "Economic Consequences of Peace." Keynes foretold the harsh consequences of the Paris Peace Conference on Germany -- predicting it would lead to future chaos.

After the Great War, America, along with other nations became much more protectionistic, making it much harder for Germany's economy to recover from the devastating consequences of the peace treaty. While protectionism here and abroard didn't cause the Great Depression, most economists agree that the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 only made matters worse, deepening what was then only a recession and prolonging the depression.

It was with that background that Keynes and other economists who joined the conference at Bretton Woods sought to promote a more open global market for trade and the flow of currency.

Bretton Woods and subsequent agreements helped bring greater political and economic stability to world, but these consensus organizations have also long been the targets of anti-globalists, such as the John Birch Society, founded in 1958.

Those views remained in the minority in the 1950s and 1960s, when the U.S. economy expanded at an average rate of 6 percent a year, and even in the 1970s and 1980s, anti-globalism was largely a fringe movement.

It became more of a leftist and anarchist cause early in the 21st century.

Most people on the right were fine with global trade until a few years ago. Then there was the 2008 financial crisis hitting right at a time when China, which joined the WTO in 2001, was becoming a bigger economic power.

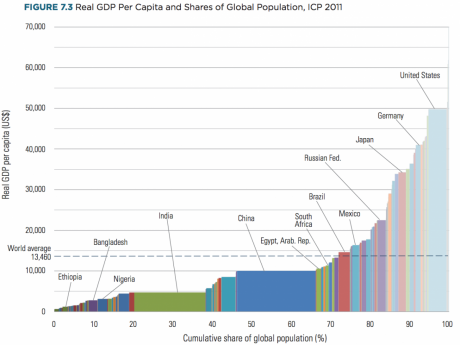

CHART: Gross Domestic Product (a measure of an economy's wealth) on a per-person basis for each country in the world, showing relative wealth and percentage of world population.

Previously:

Howard, keep this up and you

Howard, keep this up and you're going to get another press award. Or, your MS in Economics.